1) The Intihuatana – Notice the crack in the upper post from the Peruvian beer commercial film shoot a few years ago: Photo by Shawn Herring

The first time I visited the famous “lost city” in 1978 my travel companions and I disembarked from a local train at a one-room rail depot in a remote valley covered by high jungle. The spot was known as Aguas Calientes after the nearby hot springs of the same name.

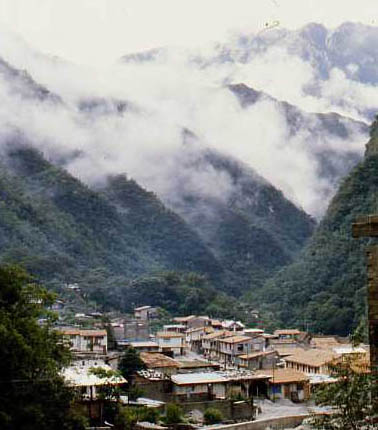

2) Aguas Calientes, 1978: photo by Craig Olivier

To reach the famous ruins on top of the mountain that overlooks the Urubamba Valley, we walked a couple of kilometers along the train track – the train made no further stops for eighty kilometers, so hiking was our only option – along the route that continued downriver to the town of Quillabamba. A bridge traversed the cranky, fast-flowing Urubamba River, which is known locally as the Vilcanota. To climb the steep switchback road to Machu Picchu most visitors opted for the public bus that departed from the far side of the steel span, but adventurous tripsters often utilized a different option, climbing a near vertical, vine-entangled path that began at the river and ended at the upper parking area near the entrance to the archeological site.

I chose the latter means of ascent, despite the hillside’s reputation as home to swarms of bushmasters, South America’s notorious venomous snake. These reptiles are not native to the area; archeologists and anthropologists speculate that the Incas or other residents of Machu Picchu may have imported the critters as a means of discouraging unwanted guests from clambering to their princely resort, haven for virgins, or whatever use the original inhabitants made of the complex. Fortunately none of these unfriendly guardians molested me during the climb.

I reached the parking lot adjacent to the site’s entrance at the same time as the bus, out of breath but heaving with adrenaline and wonder. This place had a spiritual and topographical power to it that far surpassed any other locale in Peru. With few visitors about, I was able to stand on the Intihuatana, The Hitching Post of the Sun, climb Huayna Picchu and get myself trapped at the apex of a cliff with a 3000 ft. drop on either side.

The crumbling buildings had two distinct levels of stonework – some structures were assembled from massive interlocking stone blocks, others were constructed with less precision and looked like the remains of humble workers’ huts. I remembered that the ruins had never really been lost; they are located on a 19th century Italian map, and when Hiram Bingham first arrived shepherds tended flocks of sheep and llamas within the confines of the city.

The Incas had occupied Machu Picchu but no one knew with certainty who built the citadel. Bingham removed the pre-Columbian artifacts he found to Yale University where they still languish; few other physical relics of the great puzzle remain on-site. To this day no archeologist can state with real confidence who constructed the city.

But none of these enigmas now matter. Having returned to Machu Picchu many times over the years, I have witnessed the desecration caused caused by the same governments and other agencies that brought it to the world’s attention. The site is on every must-visit list for world travelers, who add locales to their resumés in the same way that bird watchers list obscure species. I revisited Machu Picchu in April of 2009 and was astonished at the environmental degradation in the river valley, the hordes of tour groups trampling inside the ruins, the underpaid guards blasting whistles at hapless tourists who dared to scramble out-of-bounds, the vast entrance fee required to enter the site, and the brand new town in the river valley, named after the original hot springs of Aguas Calientes.

3) Peruvian honky-tonk: Davarian in front of our favorite Aguas Calientes hotel, 1999. The restaurant in the background was owned by an interesting man who believed that most tourists would indulge in illegal drugs if offered

4) The hot springs: a pool beside a cow field in 1978; today another beer commercial

When I first journeyed to Machu Picchu I took a local train that cost two or three dollars for the journey that continued to Quillabamba. This train no longer exists; landslides closed the tracks to the town in the late 1990′s and now residents downriver from Machu Picchu must travel many, many hours by public bus over treacherous roads bordered by mind-numbing precipices.

These days tourists have two options to get to Machu Picchu. There is a “backpacker” train, a sterile modern collection of comfortable wagons, or the luxury version that costs $600 for foreign tourists and $400 for Peruvians, absurd sums for both groups. Flimsy hotels that charge $100 per night line the honky-tonk streets of Aguas Calientes. Coffee shops, internet cafes, and pizzerias do their best make tourists feel at home. At every turn somebody is making a profit – the trip from town up to the ruins, a twenty minute ride, costs a much as an all-day public bus from Cusco to Puno.

5) Aguas Calientes: doesn’t look too bad from above

The gigantic quantities of money now generated by various one-day tourists, overnight guests, and the hardy individuals who walk the Inca Trail (after paying dearly for the privilege) do little for the poor local people who work the tourist trade. Rather, a consortium of private and public entities fleece the tourists as surely as hucksters work the crowd at the handicraft markets in downtown Lima. Who receives these rewards is anybody’s guess. Machu Picchu is the only Inca gold mine still producing a profit, although precious metals have nothing to do with its current riches.

As late as the 1990s the governing authorities pushed all the touristic garbage from town directly into the river, near the bridge that crosses the torrent and then climbs the hill to the ruins. You couldn’t see the site from a bus; you had to walk the route. But the smell of the trash assaulted the senses long before your eyes (not to mention the river) were similarly violated. To be fair, the impromptu dumping seemed to have stopped by 2009 although the sanitation department may have chosen to deposit the refuse further away from prying foreigners.

If you are still determined to visit a lost city in Peru, try Kuelap near Chachapoyas in Amazonas Department. Or Tucume near Chiclayo. The Nasca Lines are an outstanding sight from the air, and both Colca and Cotahuasi Canyons offer geologic vistas unparalleled in any country. As an alternative, you can follow the Urubamba River and travel through the Pongo de Mainique, the Andes ultimate gateway to the lowland jungles.

So stay away from Machu Picchu unless you wish to support both government and private corruption, the severe poverty of the Peruvians who work hard to keep the site functioning, and the questionable motives of government officials who prefer to keep the gravy train rolling. There has even been talk of installing a cable car to hoist visitors to the mountain top ever faster, presuming the whole mess doesn’t melt into the valley of the Urubamba and wash down the Amazon River into the Atlantic Ocean, where it can join Atlantis as another truly lost city.

6) Room with a view – but whose? Note the inferior, reconstructed stonework: Photo by Shawn Herring

Merci pour le post. Great job. Keep it up.

I can’t believe there was talk of adding a cable car. That is insane!

If you like the cable car idea you’ll love the Peruvian government’s freshly-announced plan to build an international airport at Chinchero!