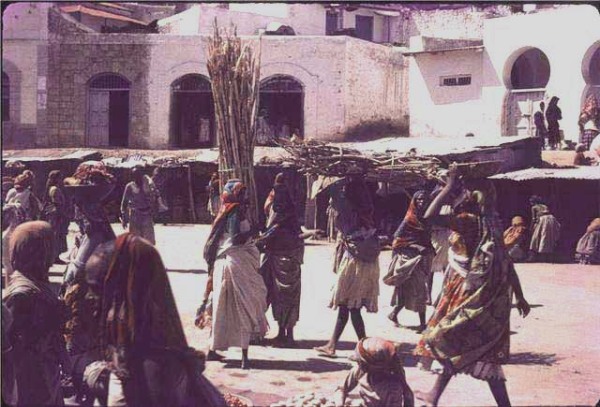

Harar street scene: Photo by Jack McGory

The hyenas circled the perimeter of the alley, audibly gnashing their teeth and giving voice to low, guttural growls. Their feet padded softly on the dirt, but the animals’ smell overwhelmed even the fetid stink from the narrow alleyway, where night soil from an open sewage canal ran through a channeled depression in the center of the lane. Over the roofs of the low cinder block buildings the faint glow of the city’s lights shined, blocking the sky and the meager starlight overhead.

I didn’t have the faintest idea how to react to the threat of the wild beasts. To think that feral creatures roamed the town after dark formed an unsettling backdrop to my already heightened sense of alertness. I sighed and moved forward warily, wishing like hell I’d thought to bring a flashlight. But then, a light may have only served to inflame the hungry scavengers into a frenzy of pack behavior. They slunk low to the ground, their fur a patchwork of mange and short, spiky hair. Insects hovered near the hyena’s elongated noses, swarming about their eyes and drooling mouths.

I didn’t have the faintest notion what actions on my part would either mollify the hyenas or perhaps set them upon me in a frenzy of violence, imagining vividly a surprise attack, and final, fleeting seconds as they tore me apart, greedily ripping chunks of flesh from my torso as they devoured his my guts, perhaps lunging first for the throat to ensure a quick demise.

Whatever had possessed me to embark on this evening stroll? The animals circled closer and I smelled their breath, redolent with the pungent odor of freshly scavenged carrion. Were they merely eating street offal, or had they found more pliable living victims close by, with their blood now whetted for meatier sustenance.

The glossy brochure I’d picked up at the Harar city tourism office proclaimed that the wild hyenas who prowled the town at night were a major attraction, harmless in their regular sojourns through the back streets as they made their way to the city gates for regular feedings by holy men whose job it was to see that the animals were kept sated and thereby inclined to leave Harar’s inhabitants unmolested.

My traveling companion, Bruce, and our new friend Jack wisely declined to join the evening tour, preferring to remain back at our hotel. There, during the daylight hours, we admired the Ethiopian fighter-bombers as they made their daily runs over the rebel positions on the front line of the Ogaden battlefront. From our comfortable room balcony we had front row seats from which to watch the carnage, rockets and bombs dropping like clouds of metallic flotsam on the hapless ethnic Somali rebels, who had advanced to within twenty kilometers of the Muslim city, hoping to free their Islamic cousins from the yoke of Mengistu Haile Mariam’s rabid dictatorship. Of course the conflict had deep roots in the animosity between the Christian Ethiopians and the Somali followers of Mohammed, and was a bitter dispute that spanned ages of sporadic warfare between the desert tribes to the east and the so-called civilized Copts from the greener highlands of Ethiopia. Like most wars, its original justifications were lost in the shrouds of history, history that was seldom written in the official annals of East African politics. Blood feuds were far more important than political and religious squabbles. In this respect, the Ogaden region was little different from a hundred other locales that I had visited over the years, from the Levant to Central Asia.

But for a traveler like myself, who craved adventure, who needed action to keep my spirit alive, Ethiopia was a prefect country to explore, with its vast unruly population repressed by a world-class strongman, yet so outside the bounds of normal human society that to call the place a country at all was a polite euphemism abetted only by mapmakers and global strategists in far-off First World capitals.

I guess I looked the part of a crazy foreigner, oblivious and impervious to the terrible circumstances I encountered in the world’s war zones and geopolitical basket cases. Yet I smelled the world around as well as did a hungry shark, a trait that occasionally served me usefully, but mostly resulted in the stench and grovel of my preferred developing countries thrusting their olfactory sensations into my brain in a never-ending assault. Frequently this worked to my advantage; tonight, however, I deeply wished that the hyenas lurking in the shadows might have had the decency to bathe before entering the inner precincts of Harar.

Toward the east I discerned a halo of light. This represented the streetlights near the main city gate, where the priests brought their scraps and garbage to feed the hyenas, so I headed in that direction. The animals followed, but as I made progress toward the Harar walls, I noticed that the creatures backed away slowly, as if realizing that their chance for a quick touristic dinner was becoming less of an option. All the stories I’d heard over the years proclaimed that hyenas dined solely on the leftovers of other carnivores, carcasses picked over by lions, leopards, and other predators. But newer theories I later watched on nature television programs would hypothesize that a different behavior was true; hyenas were the killers, and the mighty cats of the savannah filled the lesser function of the scavenger. It was a notion that would prove hard to reconcile with my schoolboy’s vision of feline prowess. But looking at those mangy prowlers who had collected nearby, I believed now that they would have killed me in a second had I assumed the behavior of prey.

Soon I arrived at the old Harar gate, a medieval structure with twin turrets connected by an overhead arch. A wooden drawbridge completed the scene, with great rusted iron chains holding the ancient beams in place. Squatting in the dirt a pair of white robed men held haunches of meat in their hands. Hyenas darted to their outstretched arms, grabbing the gristle and bones in their jaws before returning to enjoy the handouts, growling commands to their less-opportune neighbors to keep a prudent distance.

The most peculiar element to the scene was the absence of other tourists or bystanders. The “hyena men” as they were locally known, did not perform this nightly ritual for dollars or fame. Why they chose to feed the animals was a question for which I doubted I’d receive an answer.

One of the men spotted me as I stood aside in the shadows to watch the performance. “Come,” he said quietly. I obeyed.

“Here, you feed them?” The tone of the man’s voice suggested a question, but I was not certain of his intent. The priest or holy man or nut-job, whatever he was, held out a stinking piece of meat. Before I had a chance to react, a hyena darted forward and snatched the offering.

“I don’t think so.” “Maybe better I just watch, ok?”

The Ethiopian smiled. “Yes, you watch. You want to understand?”

“Sure.”

The man rose to his feet. His friend didn’t look at us, but rather kept his gaze fixed on the hyenas, who looked annoyed at the interruption of their meal. The hyenas did not move off, as I thought they might, but held their ground, waiting for the feast to continue. But I had had enough of this quaint scene, and decided to leave. The feeding was still taking place when I departed.

After returning to our squalid hotel, I propped a wooden chair against the wall of the balcony and stared down at the city. Harar had a rudimentary electrical grid, but at this hour only a few lights peeped from the houses that made up the old quarter. In the faint moonlight I saw the wall that surrounded the town. Closing my eyes to slits, I imagined myself transported to medieval times, into a pre-modern world where the twentieth century had yet to intrude.

I preferred the illusion of time-travel as opposed to thinking about the present. Not that I had traveled to Africa to escape. A person couldn’t pick a worse destination than Ethiopia to serve as an escape hatch.

* * *

A day or so later, the three of us decided to go for hike in the hills behind the city. We had no particular destination in mind, just the notion that we should stretch our legs, as the saying goes, and see what lay outside Harar.

We didn’t get far.

After walking up and over a series of low hills, we crossed a ridge top and froze in out tracks. Down in a shallow valley, hidden from the view of casual observers, a camp of some sort had been constructed. Surrounded by concertina wire and guard towers, the complex was clearly a prison or detention center. The first words that came to mind were, “concentration camp.” As we looked on the appalling sight, lines of men were being herded into the center by gun-toting guards. While we could not determine the eventual fate of the detainees, the situation did not look good. No. It looked like a horror show.

Before we had time to properly react, some guards who had apparently been patrolling the perimeter outside the camp spotted us. They ran up the hill, shouting and waving their assault rifles. Christ on a biscuit, now what were we do to?

Remembering that we were in a Muslim area, I waited until the men approached within earshot and began to holler at them in Arabic, beseeching them in the name of Allah that we were innocent bystanders who meant no harm. Ana canadi!” I cried, not knowing what else to say. “Huwah amriki!” I added, referring to Jack. “In the name of Allah the merciful, we are mere travelers, here to sniff the breeze,” I went on, using a poetic expression for travelers and pilgrims.

The guards, if that is what they were, stopped in their tracks. I said we did not come here on purpose and pointed with my arms, indicating that nothing would please us more than to beat a hasty retreat. Motioning to my brother and Jack, I quickly backed up and commenced the fastest trot I could manage while maintaining a semblance of dignity. My companions followed suit, and sweating, we backed away from the ridge and soon returned to the relative “safety” of Harar.

That episode blew us away. Harar was in the throes of a purge, although we never discovered the nature of its victims, who were likely political opponents of Mengistu.

Later, while roaming the streets of the city looking for something to eat, or perhaps to buy some basic supplies such as candles and matches – such goods were nearly unavailable in the smaller towns of Ethiopia at the time – I remember coming across a man, shackled at the ankles with a primitive wooden device that bore a superficial resemblance to the stocks that colonial American religious fanatics to punish heretical lawbreakers. The man was skinny, undernourished, and clearly in the process of becoming physically deformed from his forced “stress position” as our own military justice system currently would term the punishment. We asked him why he was shackled. Perhaps a bystander interpreted. Apparently he had been convicted of minor theft or another crime of small consequence, and his punishment was to be let loose, hog-tied, to roam the streets and beg for food. His family, if he had one, would not help his predicament. So he was like a self-mutilated beggar, forced to eke out an existence as best he could. Starvation was a real possibility. His own countrymen who were not similarly inhibited by the State had enough problems finding food. Even our group of three was hungry most of the time, as little food could be purchased, regardless of one’s financial circumstances.

One day we found a proper restaurant, shabby and unkempt. The only fare, openly displayed, was rotten raw meat, swarming with flies, and equally rotten ingera, the ubiquitous Ethiopian fermented bread. But this sample had fermented long beyond the designated time, and tasted more like decayed fish than baked flour. We were able to convince the owner of the restaurant to boil some of the meat for in oil, and we forced it down our throats, biting into the horrible ingera to help choke it down.

One one other memorable occasion we stumbled upon a huge, truck-sized pile of peanut shells from a local processing plant. Groups of women clambered over the pile of tens of thousands of shells, picking through the refuse in hopes of discovering a single peanut that had not been emptied from its casing.

Such was the lot of Ethiopia in 1977. I could say more about the street beatings, the lines of prisoners marched through the streets prodded by Mengistu’s brutal thugs, but what is the point? Madness takes the same form in all countries during times of unrest and trouble, and Ethiopia was experiencing now in its turn the horrors of human savagery,which can occur even in the most civilized countries when their leaders lose sight of rational planning and choose to force their perverted wills on the unfortunate citizens whose only crime is tor reside at the wrong time in the wrong place.

Let us hope that such events never again come to pass in our own Western countries. I am not optimistic.

You are a typical spoiled overly pampered westerner who cannot control your mental impulses to write in extremely negative tones about Ethiopia, i hope you never return and people like yourselves should stay in Paris or Rome!!! Najeeb