1) Pyramid field near Jebel Barkal

NOTE: All photos by Jack McGory except as noted

An area in the Sudan used to exist that would have ranked as a premier destination beside Kathmandu Valley in the 1960s or perhaps Bhutan in the 1950s, had any traveler the audacity to report on the place. Where? The great Bend of the Nile, located between Abu Hamed and Wadi Halfa in the northern Sudan.

In the nineteenth century, voyagers making their way from Khartoum to Egypt were obligated to pass downriver along the path of the Nile. Fortuitously for all concerned, the British built a railway that cut across the desert from Abu Hamed directly to Wadi Halfa, and a great stretch of the river was forgotten by the modern world. The railway eliminated weeks of arduous travel through cataracts, winding river channels, and a transport system that daunted all but the bravest European explorers and wanderers.

In 1977 I had the great fortune to meet a traveler who had followed this ancient route, and he told me that the region was one of the last untouristed areas remaining in northern Africa. His comments were low-key, understated, and truthful.

Having recently spent several months in Ethiopia and Kenya I decided, what the heck, why not check out the lost portion of the Nile? What was there to lose except time, perhaps my health to obscure disease, my life and worldly goods to local Muslim fanatics (the Mahdi who’s army did away with Charles Ceorge Gordon hailed from Dongola, one of the towns along the northern Sudanese Nile), or maybe a leg or two to lesser forest-dwelling cobra ankle-biters.

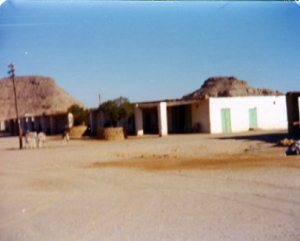

3) The town of El Khandak

As Grace Slick of the 60s group Jefferson Airplane once sang, “You can listen to a thousand different reasons why you can’t go.” I chose to listen to my heart, which told me to get there as fast as the Sudanese transportation system would allow. It only took 48 hours to travel by train from Shendi to Abu Hamed, counting breakdowns in the desert, roof-riding to admire the view, and chatting with the train personnel who must have been paid by the hour, rather than by the distance covered. A fun ride, in other words.

1) Dreadlocks on a train – heading downriver

One amenity of Sudanese travel was the availability in most towns of government rest houses, where a traveler could rest, shower, and sleep the hot days away while waiting for the next ride to show up. Abu Hamed had a wonderful establishment near the train depot, very comfortable and friendly. And when I use the word friendly in reference to the Sudan, the concept is one that implies fullness of meaning. The further one gets from civilization in the desert regions, the more wonderful, open, thoughtful, and intelligent are the inhabitants.

My journey to the lost Shangri-La in the Sahara became the closest I’d ever get to a perfect world of harmony with nature, peace, and spiritual enlightenment. Their bango, grown around Halfa Djedida, was probably the best quality I’ve sampled during my life on this planet. The Sudanese sold it by the “arm,” an amount roughly equal to the size of a man’s forearm. The cost was not particularly dear. Five bucks in local currency usually did the trick, or perhaps a bottle of Johnny Walker purchased duty free at the Khartoum Airport (I bought of few of those trade items upon my entry in-country.) These were pre-Omar Bashir days, before the crazies found their calling as corrupt feudal rulers and world class war mongers as personified by the current Sudanese president.

Still, certain events and situations stand out in my mind after all these years. In one locale, I recall sitting in the shade near the Nile and talking to an older Sudanese gentleman who spoke surprisingly good English. As it happened, he had lived in Detroit and worked in the auto industry there. “Why,” he asked, “do you white people work so hard?”

“For the money,” I replied.

“And what good is that? You suffer, you have no time to enjoy life and when you die your money stays behind. This is life without purpose.”

“Well, we have to eat and pay for housing, you know.”

“That is why I returned to the Nile. Here, we do not need your fancy houses. Here, food grows without trouble. Here, we can contemplate life, and we hope to discern the wishes of Allah. You Americans are crazy. You waste your lives, you die in poor health, and your precious time on Earth is squandered.”

I had no good answer to his astute comments. He was correct in his assessment of the Western lifestyle and grateful to have escaped it. His attitude was typical of every Nubian I had the pleasure to meet. In a sense, they were proto-hippies who practiced their values rather than merely yammering about them to others.

On another occasion, I was again sitting on the riverbank, meditating on the afternoon heat and stillness of the atmosphere. I must have remained perfectly still and quiet for an hour. Then, out of the corner of my eye, I noticed movement. A fox trotted past, between my position and river, without seeing or smelling my farangi scent. The animal approached within two or three feet and I smiled. He grinned in return, his mouth open in a perfect imitation of a human smile, and continued on his way. I had not threatened him and he had no reason to exhibit fear. I felt a connection with the land and fauna that I have never experienced since. Slowly I rose and walked away, leaving the fox to squat on his haunches and observe my departure.

Most villages had no system of drinking water, common enough at the time. Everyone, including me, bathed in the Nile, drank directly from its waters, and allowed the cool fast-flowing current to caress our bodies and minds. In the towns great ceramic urns were placed in convenient public gathering spots. They were huge, hand-thrown pottery containers, which must have taken considerable skill to produce. Every urn would have a cover, and a metal drinking cup attached via a string to the top. The protocol was simple; you took the cup, scooped water from the urn, drank your fill, then rinsed the vessel from the container, rendering it sanitary for the next customer. Of course the service was a communally organized affair, and the only sin a traveler could commit was to not to rinse the cup.

2) Village street in need of a sand blower

I never contracted even the slightest upset stomach during my journey. The Nile River has, at least in the Sudan, some kind of ancient magic to its waters that keep them clean and parasite-free. I still wonder how this is possible, but the truth of the matter was clear to everyone who lived there.

I traveled to one of the many islands in the river, huge tracts of land that appear on no maps – although these days you can probably zoom to them with Google Earth. To get there, a local man showed me the ferry, a 40 ft. wooden sailboat similar to an Egyptian felucca. The captain was asleep at the bottom of the boat, but happy to accept a few pennies to sail us to the island. He even allowed me to take the helm and steer the craft. The rudder was huge, heavy and extended far behind the transom in order to steady the boat in the current. One did not steer with the rudder, but rather maintained it in the central position while manipulating the boat’s direction by turning the lateen sail. Very simple, very efficient, very advanced nautical understanding.

We walked through a dense palm forest on the island. There were no villages as such, only the occasional collection of thatched huts. At one such compound we were invited in by a woman. She was loud, talkative, and effusive in her happiness. It seemed she had given birth a few weeks before, and in keeping with local tradition, had a rest period of 40 days where her menfolk were obligated to cater to her every whim. She also told me I was the first white person to have visited the island in living memory. I met a few of her relatives, some of whom had blue eyes. I was told that this island had once been settled by nasri or Christian peoples from far away, and who had intermarried with the native Africans. Of course, all the residents had long ago converted to Islam, but their genes told of past migrations that have been lost to the historical record.

One last memorable evening occurred, the details of which I have described in my novel, “Descending the Cairo Side.” While overnighting in a small hamlet, I happened to pass near the mosque at the center of the village, and found the townsfolk gathered in the cleared sandy space in front of the building. Never one to impose myself on other peoples’ religious and cultural practices, I attempted a retreat. However I was beckoned by the participants to sit and join them in a feast and dance, held in honor of an important person who had died seven years previously. This celebration was a rare custom from pre-Islamic days that was still carried out in Nubia. I will leave the precise details to my novel, but we feasted and danced under the night sky for hours, a unique combination of ancient African ritual and rural Saturday night fun. The village had no electricity, running water, streets that would be recognized as such, and no modern structures made of any materials except wattle and mud. The flute-playing helped to coax every witness into a trance-like state, while the dancing, with men leaping high into the air in a rhythm suggested by the flutes and drums, made for a scene from long-past recesses of the human spirit. I was astonished to have the honor to attend this occasion, and the locals told me probably no Westerner would see this event again, as the honoring of long dead men was a dying art form, and soon would disappear altogether. They spoke with eloquence and sadness about their predicted future, with the women of the village shared equally in the conversation. These women especially treated me with gentle kindness. No Muslim strictures about separation of the sexes in this part of the Sudan, at least not in those days during the 1970s.

During the trip down the bend of the Nile I traveled via every imaginable conveyance. I hopped a train for one segment, sailed on small wooden boats, covered some miles by ancient paddle wheeler, and walked more than I would have cared to had there been a choice – the season was late spring and the heat was intense, with afternoon temperatures reaching the high 40s on the Celsius scale.

5) In the pilothouse of a river boat – we spent hours with the captain and his mate on this trip, drinking endless cups of tea, puffing on bango, watching the river drift by, and ruminating about life’s greater meaning

6) Another ferry boat, somewhere on the Nile’s Bend. Shadow on left is Jack snapping the photo; my shadow is on the right

Donkey transport proved occasionally useful, but the last portion of the trip I traveled by truck along the Nile, on a roadless stretch that veered away from the river into the deep desert to avoid canyons and cliffs. On the last memorable night before reaching Wadi Halfa, we crawled through the desert without headlights because the driver thought the vehicle’s battery would last longer if he didn’t needlessly drain its electricity. We crossed the Tropic of Capricorn, and to the south I saw clearly the Southern Cross, while near the horizon to the north the Pole Star shone brightly in the night sky, with the Milky Way so intense in the moonless starry dome that the world was aglow while I witnessed the principal stars of both the northern and southern hemispheres.

I arrived at one final conclusion before dawn. Gazing at this trackless wilderness I came to understand a basic theorem of biological existence. Where life is capable of existing it will find a way to propagate and thrive, as I found my own path through Africa and into the beauty of a lost world.

7) The water wheel turns on the same axis as the Earth

8) The end of the line: modern Wadi Halfa. The old city, much honored by writers and poets, now lies deep under Lake Nasser and the reconstructed town is a poor substitute for its predecessor. Photo by Steve Routhier

Very inspiring and interesting article. I have talked to a few people who are still traveling in Sudan today, although it is quite rigorous.

What exactly is bango?

Um, bango is the local term for pot…

So jealous that you have traveled in this fascinating country… I want to get there someday!