While scouting for the first descent of the Baro River in Ethiopia, a tributary of the White Nile, I heard about a Peace Corps volunteer, Bill Olsen, 25, a recent graduate of Cornell, who decided to take a dip in the river at Gambella, a village near the South Sudan border. The locals warned to stay away from the river, which they claimed was busy with monsters. Bill swam to a sandbar on the far side of the muddy river, and sat there, his feet on a submerged rock. He was leaning into the current to keep his balance, a rippled vee of water trailing behind him, his arms folded across his chest as he was staring ahead lost in thought.

Nonetheless, I went forward with my plans to make the first descent of the Baro River.

Above, the jungle was a brawl of flora and vines and roots. Colobus monkeys sailed between treetops, issuing washboard cries.

Below, three specially designed inflatable white-water rafts bobbed in a back eddy, looking, from the ridge, like restless water bugs. There were 11 of us, all white-water veterans, save Angus. He was in the raft with me, Karen Greenwald, and John Yost, my high-school friend and partner. As the leader and the most experienced river-runner, I was at the oars.

Our raft would go first. At the correct moment we cast off — Angus coiled the painter and gripped for the ride. I adjusted the oars and pulled a deep stroke. For a prolonged instant the boat hung in a current between the eddy and the fast water. Then it snapped into motion with a list that knocked me off my seat.

“This water’s faster than I thought,” I yelled. Regaining the seat, I straightened the raft, its bow downstream. The banks were a blur of green; water shot into the boat from all sides.

Just minutes after the start of the ride, we approached the rapid. Though we’d been unable to scout it earlier…its convex edge was clad in thick vegetation preventing a full view of the river…I had a hunch it would be best to enter the rapid on its right side. But the river had different notions. Despite frantic pulls on the oars, we were falling over the lip on the far left.

“Oh my God!” someone screamed. The boat was almost vertical, falling free. This wasn’t a rapid — this was a waterfall. I dropped the oars and braced against the frame. The raft crashed into a spout, folded in half, and spun. Then, as though reprieved, we straightened and flumped onward. I almost gasped with relief when a lateral wave pealed into an explosion on my left, picking up the raft, slamming it against the nearby cliff wall like a toy, then dumping it and us upside down into the millrace. Everything turned to bubbles.

I tumbled, like falling down an underwater staircase. Seconds later, I surfaced in the quick water below the rapid, a few feet from the overturned raft. My glasses were gone, but through the billows I could make out another rapid 200 yards downstream, closing in fast. I clutched at a rope and tried to tow the raft toward shore. Behind I heard Karen: “Angus. Go help Angus. He’s caught in a rope!”

He was trailing ten feet behind the raft, a snarl of bowline tight across his shoulder, tangled and being pulled through the turbulence. Like the rest of us, he was wearing a sheathed knife on his belt for this very moment — to cut loose from entangling ropes. His arms looked free, yet he didn’t reach for his knife. He was paralyzed with fear.

I swam back to Angus, and with my left hand seized the rope at his sternum; with my right I groped for my own Buck knife. In the roiling water it was a task to slip the blade between Angus’s chest and the taut rope. Then, with a jerk, he was free.

“Swim to shore,” I yelled.

“Swim to shore, Angus,” Karen cried from the edge of the river.

He seemed to respond. He turned and took a stroke toward Karen. I swam back to the runaway raft with the hope of once again trying to pull it in. It was futile: The instant I hooked my hand to the raft it fell into the pit of the next rapid, with me in tow. My heart, already shaking at the cage of my chest, seemed to explode.

I was buffeted and beaten by the underwater currents, then spat to the surface. For the first time, I was really scared. Even though I was swashed in water, my mouth was dry as a thorn tree. I stretched my arms to swim to shore, but my strength was sapped. This time I was shot into an abyss. I was in a whirlpool, and looking up I could see the surface light fade as I was sucked deeper. At first I struggled wildly, but it had no effect, except to further drain my small reserves. My throat began to burn. I became disassociated from the river and all physical environments. Then I became aware of a strange thing. The part of me that wanted to panic began to draw apart, and then flew away. There no longer seemed any but the flimsiest connection between life and death. I went limp and resigned myself to fate. I seemed to witness it all as an onlooker.

In the last hazy seconds I felt a blow from beneath, and my body was propelled upward. I was swept into a spouting current, and at the last possible instant I broke the surface and gasped. I tried to lift my arms; they felt like barbells. My vision was fuzzy, but I could make out another rapid approaching, and I knew I could never survive it. But neither could I swim a stroke. The fear of death was no longer an issue, for that seemed already decided. But I kept moving my arms automatically, for no better reason than that there was nothing else to do. It felt like an age passed like this, my mind stuck in the realization of my fate.

Then, somehow, a current pitched me by the right bank. Suddenly branches and leaves were swatting my face as I was borne around a bend. I reached up, caught a thin branch, and held tight. I crawled to a rock slab and sprawled out. My gut seized, and I retched. A wave of darkness washed through my head, and I passed out.

When my eyes finally focused, I saw figures foraging through the gluey vegetation on the opposite bank. John Yost was one; Lew Greenwald, another. He had been in the third boat, and seeing him reminded me that there were two boats and seven people behind me. How had they fared?

John paced the bank until he found the calmest stretch of river, then dived in; the water was so swift that he reached my shore 50 yards below his mark. He brought the news: The second raft, piloted by Robbie Paul, had somehow made it through the falls upright. In fact, Robbie was thrown from his seat into the bilge during the first seconds of the plunge, and the raft had continued through captainless. The third boat, handled by Bart Henderson, had flipped. Bart was almost swept under a fallen log, but was snatched from the water by the crew of Robbie’s boat.

All were accounted for — except Angus Macleod.

I was leery of bringing along anyone outside my tight-knit, experienced coterie on an exploratory, but the lure of capital was too strong. Joel, however, would never make it out onto the Baro. He traveled with us to the put-in, took one look at the angry, heaving river, and caught the next bus back to Addis Ababa. He may have been the smartest of the lot.

Angus was altogether different. While Joel smacked of presentation and flamboyance, Angus was taciturn and modest. He confessed immediately to having never run a rapid, yet he exuded an almost irresistible eagerness and carried himself with the fluid bounce of a natural athlete.

He was ruggedly handsome and had played professional soccer, and though he had never been on a river, he had spent time sea kayaking the Jersey shore. After spending a short time with him I could see his quiet intensity, and I believed that — despite his lack of experience — he could handle the trip, even though there would be no chance for training or special conditioning before the actual expedition.

Once in Ethiopia, Angus worked in the preparations for the expedition with a lightheartedness that masked his determination. On the eve of our trip to Illubabor Province — a 17-hour bus ride on slippery, corrugated mountain roads — I told Angus to make sure he was at the bus station at 7 a.m. for the 11 a.m. departure. That way we would all be sure of getting seats in the front of the bus, where the ride wasn’t as bumpy or unbearable stuffy. But, come the next morning, Angus didn’t show until 10:45. He got the last seat on the bus and endured.

Later, after the accident, standing on the bank of the river with John Yost, I wondered if I’d made the right decision about Angus. We searched the side of the river where I’d washed ashore; across the rumble of the rapids we could hear the others searching. “Angus! Are you all right? Where are you?” There was no answer. Just downriver from where I’d last seen him, John found an eight-foot length of rope — the piece I’d cut away from Angus’s shoulders.

After an hour John and I gave up and swam back across the river. We gathered the group at the one remaining raft, just below the falls.

“He could be downstream, lying with a broken leg,” someone said.

“He could be hanging onto a log in the river.”

“He could be wondering in a daze through the jungle.”

Nobody suggested he could be dead, though we all knew it a possibility. All of us had a very basic, and very difficult, decision to make, the kind of decision you never want to have to make on an expedition: Should we stay and look for Angus, or should we get out while there was still light? Robbie, Bart, and George and Diane Fuller didn’t hesitate — they wanted out. Karen Greenwald wanted to continue searching, but she seemed hysterical. Against her protests, we sent her out with the others.

That left five of us — Lew Greenwald, Gary Mercado, Jim Slade, John Yost and me. We decided to continue rafting downstream in search of Angus on the one remaining raft. I had mixed feelings — suddenly I was scared to death of the river; it had almost killed me. The ambient sentiment was that we could very well die. Yet I felt obligated to look for a man missing from a boat I had capsized, on an expedition I had organized. And there was more: I felt I had to prove to myself that I had the right stuff, that I could honor the code, and do the right thing.

But the river wasn’t through with us. When we were ready to go, I climbed into the seat of the raft and yelled for Jim to push off. Immediately we were cascading down the course I’d swum earlier. In the rapid that had nearly drowned me, the raft jolted and reeled, kicking Gary and me into the brawling water.

“Shit — not again,” was my only thought as I spilled out of the raft into another whirlpool. But this time I had the bowline in hand, and I managed to pull myself quickly to the surface. I emerged beside the raft, and Lew grabbed the back of my life jacket and pulled me in. My right forearm was lacerated and bleeding. Jim jumped to the oars and rowed us to shore.

My injury wasn’t bad — a shallow cut. But Gary had dislocated his shoulder; he’d flipped backward over the gunwale while still holding onto the raft. He was in a load of pain, and it was clear he couldn’t go on. Lew — thankful for the opportunity — volunteered to hike him out.

John, Jim and I re-launched and cautiously rowed down a calmer stretch of the river, periodically calling out for Angus. It was almost 6:00 PM, and we were just three degrees north of the equator, so the sun was about to set. We had to stop and make camp. It was a bad, uncomfortable night. Between us, we had a two-man A-frame tent, one sleeping bag, and a lunch bag of food. Everything else had been washed into the Baro.

That morning we eased downriver, stopping every few minutes to scout, hugging the banks, avoiding rapids we wouldn’t have hesitated to run were they back in the States. At intervals we called into the rain forest for Angus, but now we didn’t expect an answer.

Late in the afternoon we came to another intimidating rapid, one that galloped around a bend and sunk from sight. We took out the one duffel bag containing the tent and sleeping bag and began lining, using ropes to lower the boat along the edge of the rapid. Fifty yards into the rapid, the raft broached perpendicular to the current, and water swarmed in. Slade and I, on the stern line, pulled hard, the rope searing our palms, but the boat ignored us. With the snap of its D-ring (the bowline attachment), it dismissed us to a crumple on the bank and sailed around the corner and out of sight.

There was no way to continue the search. The terrain made impossible demands, and we were out of food, the last scraps having been lost with the raft. We struck up into the jungle, thrashing through wet, waist-high foliage at a slug’s pace. My wound was becoming infected. Finally, at sunset the light folded up on itself and we had to stop. We cleared a near-level spot, set up the tent, squeezed in, and collapsed. Twice I awoke to the sounds of trucks grumbling past, but dismissed it as jungle fever, or Jim’s snoring.

In the morning, however, we soon stumbled onto a road. There we sat, as mist coiled up the tree trunks, waiting. In the distance we could hear the thunder roll of a rapid, but inexplicably the sound became louder and louder. Then we saw what it was: 200 machete-wielding natives marched into sight over the hill. General Goitom, the police commissioner of nearby Motu, hearing of the accident, had organized a search for Angus. Their effort consisted of tramping up and down the highway — the locals, it turned out, were more fearful of the jungle canyon than we were.

I remember very little of the next week. We discovered that Angus held a United Kingdom passport, and I spent a fair amount of time at the British embassy in Addis Ababa filling out reports, accounting for personal effects, and communicating with his relatives. John and Jim stayed in Motu with General Goitom and led a series of searches back into the jungle along the river. We posted a cash reward — more than double what the villagers earned in a year — for information on Angus’s whereabouts. With financial assistance from Angus’s parents, I secured a Canadian helicopter a few days after the accident and took several passes over the river. Even with the pilot skimming the treetops, it was difficult to see into the river corridor. The canopy seemed like a moldy, moth-eaten army tarpaulin. On one flight, however, I glimpsed a smudge of orange just beneath the surface of the river. We made several passes, but it was impossible to make out what it was. Perhaps, I thought, it was Angus, snagged underwater. We picked as many landmarks as possible, flew in a direct line to the road, landed, cut a marker on a tatty dohm palm, and headed to Motu.

A day later John, Jim and I cut a path back into the tangle and found the smudge — a collection of leaves trapped by a submerged branch. We abandoned the search.

In November I got a call from a friend, a tour operator. A trek he’d organized to the Sahara had been canceled by the Algerian government, and his clients wanted an alternative. Would I be interested in taking them to Ethiopia for a trek? Two weeks later I arrived in Addis Ababa, where I met up with John Yost, Jim Slade, and a trainee-guide, Gary Bolton, fresh from a SOBEK raft tour of the Omo River. They were surprised to see me, here where nobody expected I would return.

By late December, after escorting a commercial trek through the Bale Mountains of southern Ethiopia, John, Jim, and I were wondering what to do next, and the subject of the unfinished Baro came up. The mystery of Angus still gnawed at all of us. I confessed that over the months, sometimes in the middle of a mundane chore — taking out the trash, doing the laundry — I’d stop and see Angus’s frozen features as I cut him loose. In weak moments I would wonder if there just might be a chance that he was still alive. And I’d be pressed with a feeling of guilt, that I hadn’t done enough, that I had waded in waist deep, then turned back. And I wondered how Angus had felt in those last few minutes — about himself, about me. Jim and John admitted to similar feelings, and we collectively decided to try the Baro once again. We needed a fourth, and Gary Bolton agreed to join as well.

This time we put-in where I had taken out almost two years before, at the terminus of a long jungle path. Again, we had a single raft, with the minimum of gear to make portaging easier. The river pummeled us, as it had before, randomly tossing portages and major rapids in our path. But during the next few days, the trip gradually, almost imperceptibly, became easier. On Christmas morning I decorated a bush with my socks and passed out presents of party favors and sweets. Under an ebony sapling I placed a package of confections for Angus. It was a curiously satisfying holiday, being surrounded by primeval beauty and accompanied by three other men with a common quest. No one expected to find Angus alive, but I thought that the journey — at least for me — might expunge some doubt, exorcise guilt. I wanted to think that I had done all humanly possible to explore a death I was partly responsible for. And somehow I wanted him to know this.

As we tumbled off the Abyssinian massif into the Great Rift Valley of Africa, taking on tributaries every few miles, the river and its rapids grew. At times we even allowed ourselves to enjoy the experience, to shriek with delight, to throw heads back in laughter as we bounced through Colorado-style white water and soaked in the scenery. Again, we found remnants of the first trip – a broken oar here, a smashed pan there. Never, though, a hint of Angus.

After one long day of portaging, I went to gather my wetbag, holding my clothes, sleeping bag and toilet kit, and it was nowhere to be found. Apparently, it had been tossed out during one of the grueling portages. I trekked back upstream for a couple miles, but could find nothing, and it was getting dark, so I picked my way back to the raft and the plain pasta dinner John was cooking. At that moment, I had no worldly possessions, save the torn shorts I was wearing, my socks and tennis shoes, and the Buck Knife that hung from my pants. I slept in a small cave that night, rolled up like a hedgehog, with no sleeping bag, no pad, but I slept well. With the morning, I awoke fresh and energized, ready for the day, and though I had practically nothing to call my own, I felt a richness for the moment…I was with friends, on a mission, and was touching something primal. In an odd way, this all seemed liberating…no accoutrements to weigh down the soul…just a clear, present reason for going forward, for being. And I allowed something that would be called joy to wash over me.

On New Year’s Eve we camped at the confluence of the Baro and the Bir-Bir rivers, pulling in as dusk was thickening to darkness. A lorry track crossed the Baro opposite our camp. It was there that Conrad Hirsh, the professor from the second Baro attempt, had said he would try to meet us with supplies. We couldn’t see him, but Jim thought there might be a message waiting for us across the river. “I think I’ll go check it out,” he said.

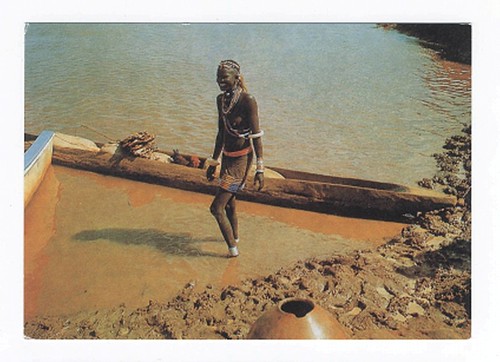

“Don’t be a fool,” John warned. “We’re in croc country now. You don’t want to swim across this river.” We weren’t far from where Bill Olsen, the Peace Corps volunteer, was chomped in half while swimming.

“Conrad arrived three day ago, waited two, and left this morning,” he said, his body still dripping from the swim.

“You fool! I knew you couldn’t disappear now — you owe me $3.30 in backgammon debts.” I clucked with all the punitive tone I could muster.

The following day we spun from the vortex of the last rapid into the wide, Mississippi-like reaches of the lower Baro. Where rocks and whirlpools were once the enemy, now there were crocodiles and hippos. We hurled rocks, made threatening gestures, and yelled banshee shrieks to keep them away. Late in the day on January 3, 1976, we glided into the outpost town of Gambella. The villagers there had neither seen nor heard of Angus Macleod.

I never told Angus’s relatives of our last search; we didn’t find what might have given them solace. What I found I kept to myself, buried treasure in my soul. It was the knowledge of the precious and innate value of endeavor.

I wanted to believe that when Angus boarded my tiny boat and committed himself, he was sparked with life and light, that his blood raced with the passion of existence –perhaps more than ever before. As we first launched our rafts on the Baro ten of us thought we knew what we were doing: another expedition, another raft trip, another river. Only Angus was exploring beyond his being. Maybe his was a senseless death, moments after launching, in the very first rapid. I would never forget the look of horror in his eyes as he struggled there in the water. But there were other ways to think about it. He took the dare and contacted the outermost boundaries. He lost, but so do we all, eventually. The difference — and it is an enormous one — is that he reached for it, wholly.